| ||

| Dublin Bay and Wicklow Mountains from Howth [ALAMY] |

On Easter Monday, 24 April 1916, my father's family were picnicking on Howth Head when the Rising broke out. Unfortunately no written records survive of the Diamond family's experience of Easter Week 1916, but the story was passed down to me by my father, John Gilbert ('Jack'), who was 18 months old at the time.

My grandfather, Henry ('Harry') Diamond was Scottish and my grandmother Nellie also came from a Scottish family, the Irvines, but had been born in England. Harry was born in Hamilton, Ayrshire, in 1876 but his father, a gardener, moved a few years later to work on Clober Estate, in Milngavie, just north of Glasgow. Harry attended the High School of Glasgow and Glasgow University, graduating with an MA in 1899. He did well in the British government's civil service entrance exams and was given the choice of being posted to Dublin or to Delhi. Harry chose Dublin. He was appointed as a first class clerk to the Local Government Board of Ireland, and developed a speciality in Poor Law Administration; he seems to have been closely involved in setting the rates for the country's first old age pensions, as well as in overseeing management of workhouses.

Harry's Scottish Presbyterian roots remained very important and he became a member of the United Free Church of Scotland in Lower Abbey Street, Dublin. It was probably through church activities that he met Nellie Irvine, a member of the church choir. Nellie was born in Bloomsbury, London, in 1882, to James Anderson Irvine, a journeyman tailor, and his wife Harriett McCormack, a dressmaker. But as a small child Nellie had been adopted by her father's sister Mary and her husband James, a grocer. They took her to live with them first in Scotland, where they spent short periods in Glasgow and Barrhead - her uncle worked for the huge Barrhead Co-operative Society and they can be found in the 1891 census living above one of the town's several Co-op branches - and then to Dublin. It seems that James and Mary Gilbert were unable to have children and adopted Mary's niece to fill the gap as well as to give her a better education than her parents could afford - she was certainly much loved. However her parents went on to have three more daughters (one of whom, Isabella, died aged seven in slightly mysterious circumstances after a fall at school in Kentish Town) and a son. The families stayed in close contact and photographs indicate frequent visits to one another's homes in Dublin, London and Scotland.

Nellie trained as a secretary and got a job as what would now be called a PA to J C M Eason, the grandson of the founder of Eason & Son, the Irish equivalent of W H Smith - in fact the company was originally established as Smiths' Irish operation, but Charles Eason and his son acquired it in 1886. John Charles Malcolm Eason joined the firm after graduating from Trinity College Dublin in 1901, and went on to become its managing director. When Nellie Irvine worked for him he was running the wholesale stationery department, based in Middle Abbey Street, just round the corner from the company's main premises in Lower Sackville Street, which in turn was two doors away from the General Post Office.

Harry Diamond and Nellie Irvine became engaged in 1907 and Nellie stopped working at Easons in April 1908. Her colleagues bought her a set of cutlery from Weir's in Grafton Street as a wedding present; this is the letter that her boss J C M Eason sent with it:

The marriage took place in the United Free Church of Scotland in July 1908 and was followed by a honeymoon tour to Switzerland.

|

| Mr and Mrs Henry Diamond, July 1908 |

|

| Diamond-Gilbert family group 49 Lindsay Road |

The family loved picnics and seaside and country walks, and the Hill of Howth, with its beaches, steep paths through drifts of bracken and heather around the grassy summit and spectacular cliff-top views south across Dublin Bay to the Wicklow Mountains, north to the Mountains of Mourne, and out over the Irish Sea, was a favourite destination. The weather on Easter Monday 1916 was beautiful - the sea would have been sparkling and the headlands blazing with yellow gorse blossom.

|

| Howth Head [ALAMY] |

It's quite likely that 'Auntie and Uncle' James and Mary Gilbert were with Harry and Nell and the two children on their excursion. But the only detail to have passed down in family lore about that day is that when the time came to leave the trams had stopped running because of the disturbances in the city centre and it was difficult for them to get home. So what happened? Perhaps the trains were still running, or they may have managed to get a horse-drawn cab or trap - Howth is not far from Glasnevin, but walking would have been impossible with a toddler and a young child.

Easter Tuesday was probably a normal working day for Harry, and without the benefit of today's electronic media to report on what was happening in the city centre he probably set off for his office as usual - no doubt on foot, or perhaps by bicycle - he was a very fit, energetic man who would never have taken a tram if he could have avoided it. As a civil servant in the local government board he was almost certainly based in the Custom House, the elegant Georgian building designed by James Gandon which is a major landmark on the bank of the River Liffey a few hundred yards downstream from O'Connell Bridge.

The Volunteers had no interest in the Custom House and made no attempt to capture it, but it overlooked Liberty Hall, the headquarters of James Connolly's Citizen Army, so in the early days of the rebellion it was used as a base for British troops, who bombarded Liberty Hall with machine-gun fire from the parapets around its dome, joined in the assault by the Royal Navy's gunboat Helga, moored just opposite the Custom House. Liberty Hall was reduced to rubble, as were countless buildings along the quayside and the surrounding streets. The Custom House survived, though it was burned down by the IRA a few years later in the War of Independence.

As the British bombardment of Sackville Street intensified towards the end of Easter Week, Nellie Diamond's former place of work, Eason's, was completely destroyed. At first the Eason family had been most concerned about the difficulty of maintaining newspaper deliveries, as the packet boats had stopped running to and from England, and then about looting. The directors of the firm loved on the south side of the city and it was not until Sunday 30 April, according to L M Cullen's history of Eason & Son, that Charles and J C M Eason were given permits at Dalkey Town Hall to travel in to Dublin the next day, when 'it was possible to go by car as far as O'Connell Bridge, and from there to Abbey Street, where they saw their premises totally destroyed "but the return building, consisting of the 3 strong rooms was standing and the iron doors were closed"'.

Lower Abbey Street and the area around the United Free Church was also devastated by the conflict. As a member (very much the youngest!) of the church's management committee Harry Diamond would have been closely involved in repairing damage and in the immediate relief efforts to help local residents who had lost their homes; mission to the impoverished surrounding community was an important aspect of the church's work. A lover of art, he must have been deeply saddened by the loss of the Royal Hibernian Academy, not far from the church, and all its treasures.

|

| Royal Hibernian Academy, Lower Abbey Street, 1916 |

On Tuesday evening, Irwin writes, 'we sat indoors conversing in low tones, listening now to the rattle of machine-guns as the cordons commenced to close in on the centre of the city, The rifle shots of the Volunteers were still, however, clearly distinguishable. The night passed with sporadic shooting throughout, and now a sinister red glare glowered over the city, Afterwards we found it was Lawrence's Photographic & Toy Stores, where looters had set alight fireworks and rockets ...

'Wednesday morning we were fully wakened from a troubled sleep to the sound of cannonade. It came from the direction of the east city where the gunboat Helga bombarded Liberty Hall ... It was evident to us, hapless listeners, confined mostly to our homes, that the military were now fully engaged in an offensive against the insurgents, The food situation in this district was now deteriorating. The few shops open were now sold out, but a local mill-store was able to supply flour. The nuns at Cabra Convent worked overtime in baking bread and anybody willing to undertake the hazards of the journey were [sic] able to purchase a loaf or two regardless of sect or religion but, of course, such supplies could not go far. Dairy men, however, still got through and it was amusing to see well-dressed citizens, who normally would not even carry a parcel, staggering home under a sack of flour and bag of potatoes ... One did not know what was going to happen next. To me, at the time, the city had undergone a horrible transformation.'

Later in the week Irwin is able to spend a day with a married sister. 'She was quite a good pianist and when immediate household tasks were completed I persuaded her to run through popular melodies on the keyboard. It helped to drown the sounds of conflict and for a time afforded relief from the prevailing anxieties of life and death. For a long time afterwards I preserved a piece of the soda bread she baked during the fateful week. I fear she was an indifferent cook at the time ... it was as hard as a brick. I still think I should have preserved it for the 1916 collection in our national museum. It was one of the minor horrors of the rising.'

| |

|

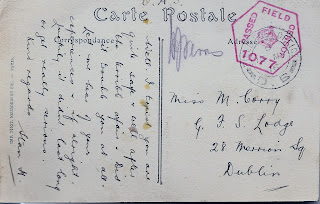

Wilmot Irwin's book also illuminates the two scraps of paper illustrated above which come from my family collection. 'It was Thursday when troops of the Staffordshire regiment arrived to set up a military post at the North City Mill at Cross Gun's Bridge. Very young territorials they were, with somewhat shoddy equipment, although their rifles were of the current Lee-Enfield pattern. They would not let anybody pass beyond the bridge without a pass and these were not easy to obtain. The pass was a roughly scribbled page from an officer's notebook signed with his name and rank - usually a 2nd lieutenant. People were friendly to the soldiers and brought them tea and bread from their own scanty hoards.'

As the week progressed Glasnevin continued to be quiet apart from occasional sniping. 'My brother-in-law - still wearing his uniform - went into the garden of the house next door for a game of croquet ... and had a very narrow escape. A bullet whistled by his head, presumably from the Whitworth Road area where snipers had been very active and indeed continued up to the surrender and beyond. Needless to say, the croquet game was discontinued and everybody trooped indoors once more.'

But the residents of Lindsay Road could hear the battle raging in the city centre. 'The almost incessant machine-gun fire and the whine and explosions of artillery told their own tale in eloquent terms ... The Republic was coming into being in an agony of flame and turmoil ... [on Friday] the artillery fire seemed to have intensified during the night and one could clearly hear the fall of masonry after the explosions. It was evident to us hapless listeners that nothing could live in that crescendo of shell fire. Some time after mid-day the roar of cannonade died down and then finally ceased, though stray shots were still discernable. Rumours began to multiply and soon later in the afternoon, reports were spread that the rising had ended and that the surviving insurgents had surrendered.'

| |||

| 47 and 49 Lindsay Road when new, c. 1907 |

The following Wednesday Irwin was able to get into town for the first time. 'The sight of Lower Sackville Street with the odour of burnt wood and debris of all kinds was enough to make angels weep. All the old familiar landmarks were gone. The General Post office, Elvery's Elephant House, the D.B.C Restaurant, the Metropole Hotel,m the Coliseum Theatre, where I had spent many enjoyable evenings, and the old Waxworks Exhibition in Henry Street, so often a haunt in winter months, were all gone on dust and debris.'

Lindsay Road was not far from one of the city's main cemeteries. 'It was very melancholy living in Glasnevin in those days immediately after the rising as funeral corteges followed one another in quick succession,' Irwin recalled. 'Horse-drawn vehicles followed by lines of carriages and cabs. The horses were plumed. Black for married deceased and white plumes for the young and single.'

|

| Lindsay Road 2014 [CLARE STEVENS] |